"I want to work with you"

was the best love letter to Mr. Itoi.

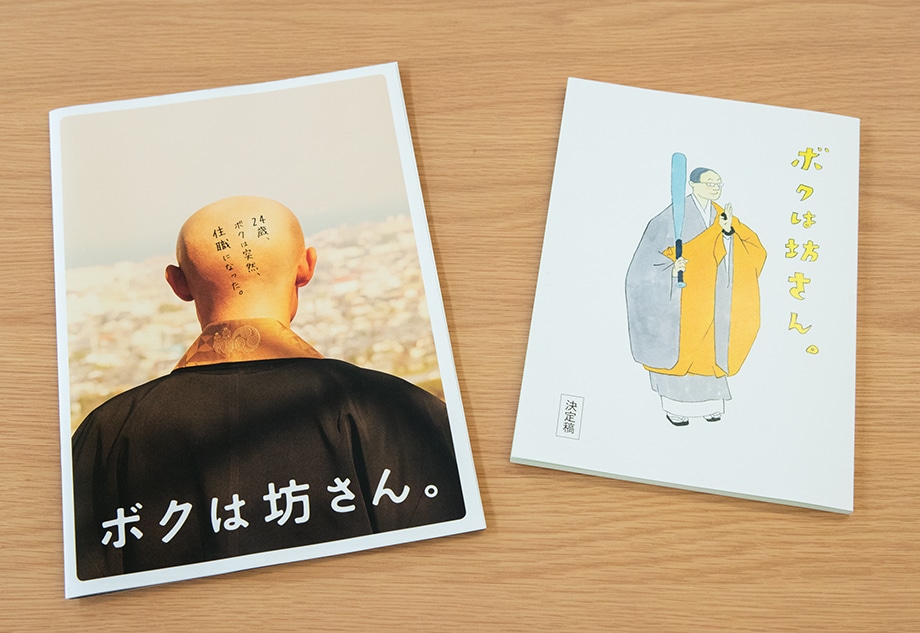

I read Shirakawa's book 『ボクは坊さん。』. It really made me feel that Buddhism is something familiar to us, something that is useful in our daily lives, and it was very interesting.

Shirakawa:Thank you. That book is based on a series in the "Hobo Nikkan Itoi Shinbun(Hobonichi)," but when I was writing for "Hobonichi," I had an own rule not to write about Buddhism.

Because I thought it would close interest for readers. I think that worked out to a certain extent. When I was making them into a book, I initially submitted the same ideas as I had in "Hobonichi," but the person in charge at the publishing company, Mishimasha, said, "I think you can take it one step further," and they asked me, "Why don't you rewrite it from the beginning again?" I thought that was a bit of a pain (laughs).

Even though I had already serialized hundreds of times (laughs).

Shirakawa:But in the end, that suggestion turned out to be a great idea. It's true that the texts you read on the web and in books are completely different. When I wanted to add new ideas to it, I used words from Kobo Daishi from 1200 years ago and words from Buddha from 2000 years ago, and it fit perfectly.

Did you add words to existing texts? I didn't think of it that way.

Shirakawa:I was surprised when I was writing it too. Readers who are not monks or Buddhism fans said that Buddha's words really touched them, and that they "loved reading them" or "I named my child Sora(from part of Kukai’s name)." In that sense, I'm glad that I was able to express Buddhism, which has been considered as something stiff, in a softer way.

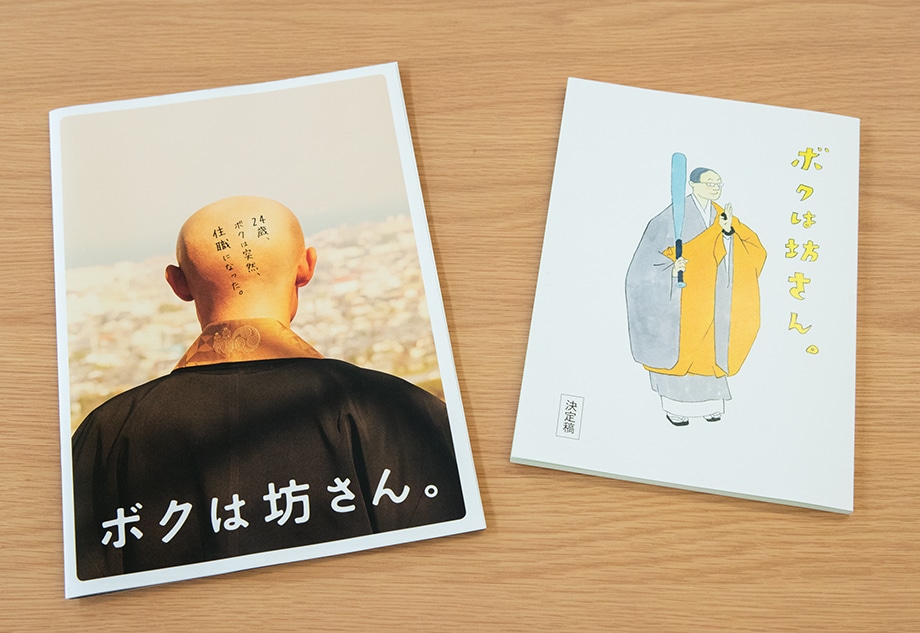

Script and pamphlet of『ボクは坊さん。』made into a movie.

Did Mr. Itoi ask you to write the "Hobonichi" serialization from the start?

Shirakawa:No, I brought it to him. I had been an avid reader of Hobonichi since I was a student, but when I became a chief priest at the age of 24 after my grandfather passed away, I was really encouraged by Hobonichi. They were trying to communicate in a new way. It wasn't harsh, and it wasn't too tense, which connected to my situation at the time. So I wrote Mr. Itoi an email saying, "Thank you. I've been reading your magazine for years," but as I was writing, I felt like coming up with a proposal (laughs). I thought it would be interesting if Hobonichi had a story about a monk who became a chief priest at the age of 24. However, I didn't really think it would actually happen, and I thought writing that I wanting to work together was the best love letter. I wrote an email saying, "I've never written anything before, but I'll give you a proposal, so could you read it?" and he replied, "I'd like to read it." So I wrote a paragraph about how life at a temple is like a role-playing game, and sent it to him, and he said, "That's interesting, let's serialize this."

So that's how it was. I didn't know it was a proposal you brought in yourself.

Shirakawa:I was properly assigned an editor. I wrote about 230 times, and for the first 100 or so, I always got a reply from Mr. Itoi.

Every time?

Shirakawa:Almost every time. And it was at 3 or 4 in the morning. At the time, Eikichi Yazawa and Takuya Kimura were appearing in "Hobonichi," and I was definitely the least well-known person. He would tell this unknown person that this part was interesting, this part was hard to understand, or maybe we should not make an announcement this time. I was impressed by how much effort he puts into that media, and how sincerely and directly he puts effort into his work and creativity.

Humans have been praying since ancient times.

This time, I would like to cover the pilgrimage, but we can read basic explanations in other books and articles, so I would like to hear "Shirakawa talks about pilgrimage." You yourself are a pilgrim, aren’t you?

Shirakawa:Yes. I do this in small increments, for example three nights and four days or one night and two days. When I was younger, I used to pilgrimage by car, but now I walk around in parts, and I'm serializing the stories on a website "Gendai Business".

Is it normal for monks go on the pilgrimage?

Shirakawa:On a pilgrimage, you can see sightseers, core fans and devout believers all coexist. There are monks in training, mountain ascetics called shugenja, girls who love temples and shrines like Goshuin Girls, and groups of old people.

You've done it many times, haven't you?

Shirakawa:It's only been about four times. I don't usually feel like I'm exhausted, but when I walk the old roads of the pilgrimage, I feel like I'm "recovering," or something like that.

Recovering. Is it that something is being healed?

Shirakawa:Rather than healing, it feels like something more overall is being restored. I sometimes feel that way as if a dam had burst. Sometimes it is tough though. Like when it rains, or I'm not feeling well, or it's hard to keep walking all day. In those situations, I realize that I'm an animal and really powerless in front of the threat of nature. It feels like both are there.

Is the power of nature greater than just visiting temples?

Shirakawa:No, but I think the interesting thing about pilgrimage is that there is also the act of praying at the temple. If you want to get in touch with nature, you can climb a mountain nearby or there are many other places, but it's interesting to pray at the midpoint. I think humans have been praying since ancient times. When someone dies, we would offer flowers and pray, and it's always been a part of our lives, but nowadays, for example, if you live an ordinary life in Tokyo, you probably don't have many opportunities to pray. I think it would be great to occasionally go on the Shikoku Pilgrimage, walk through nature and the city, and find a place to pray here and there. I think the reason why tens of thousands of people from all over Japan and the world gather in Shikoku every year is because Japan’s religiosity is so tightly concentrated here.

"It doesn't matter who you are"

Some people can't stop crying at the hospitality.

You have pilgrims here almost every day, right?

Shirakawa:Since my grandmother got married, there hasn't been a single day without someone coming to pray, even during the war and typhoons.

How many years has that been going on?

Shirakawa:She's about 90 years old, but I think she got married when she was about 20. So it's been about 70 years. This year (2018) was a year with many typhoons, but there hasn't been a day when no one came.

On the day of interview, pilgrims were constantly visiting EIFUKUJI

Even at the end of the year and the New Year holidays. It's amazing. When you think about it, are Japanese people surprisingly religious?

Shirakawa:Yes, many people claim to be non-religious, but I think they are unconsciously very religious. I think this is reflected in an interesting way in Shikoku. In Buddhism and religion, there is a concept of "giving what you have," like a gift, but in reality, it is difficult to say, "I'll give you half of my savings account." However, in Shikoku Pilgrimage, there is a culture of hospitality, and even if you don't know who the other person is or what they have done, it is still common to say, "You are a disciplinant, so please eat this" or "Please take this." It's amazing when you think about it.

Shirakawa:There are some unwritten rules in Shikoku Pilgrimage, for example, you don't ask, "Why are you praying here?" Maybe it's because the other people have all kinds of circumstances and some don't want to be touched. It is often said among religious people that "what not to say is more important than what to say," and when I look at social media these days, I like it quite a bit (laughs), but I think this "what not to say" spirit is something that is lacking in Japan right now.

They don't ask "Who are you?" or "Why are you on the pilgrimage?" It's true that it may be the opposite of social media culture.

Shirakawa:But many people talk about themselves, and when I listen to their stories, I find that many pilgrims have lost confidence. They've lost their love, they've lost their jobs. Just when they thought they couldn't do anything, someone said, "I don't know who you are, but here you go," offering them a meal or money with nothing in return, they couldn't stop crying. They say, "It doesn't matter who I am." I don't think that everyone is a good person, including myself (laughs), but it's the strength of traditional customs that makes it possible.

Is this culture of hospitality ingrained in the people of Imabari?

Shirakawa:I think it's the whole Shikoku Pilgrimage. The idea is that pilgrims are training on your behalf.

Doesn't it mean you're good at hospitality on a daily basis?

Shirakawa:I don't know about that (laughs). But humans have a surprising desire to accumulate merit. I think that people who volunteer are also aware that there is an irreplaceable joy in being useful to others. It feels good to be useful and receive thanks from others. It's not an egoistic joy, but it seems to be something that makes them really happy. In the case of the Shikoku Pilgrimage, it's not something that individuals do of their own accord, it's rooted in the culture. I don't know who you are. I think the fact that they can do it without having been helped before or anything like that is the strength of tradition, Buddhism, and the pilgrimage. After all, it's not something that "I started".